SEARCH THE ENTIRE SITE

Our Heroine

By Lionel Ruffel

In the beginning was a first fable. It is three hundred, one thousand, or even thirty thousand years old. It has no origin. It is pure matter, medium, milieu. It runs through us wherever we may be, and we constantly replay it, over and over. Even before we speak, we feel it. It is the most beautiful fable of them all, the fable of fables—it contains and welcomes all the others. After much searching, to me, there seems to be nothing closer to it than a cell or a matrix, overflowing with life, constantly moving within its own boundaries. It is life itself.

We needed a magic number for it, a number that would be as powerful as seven or three—that would be even more powerful than them. This number—you guessed it—is one thousand and one, 1001: the simplest, the most graphic, the most beautiful palindrome of them all. A code inscribed within the first mention of it there ever was, in Baghdad, more than ten centuries ago. It then competes with the number one thousand, which is written in the title of a Persian work, Hezār Afsān, later reused in Arabic, Alf Khurafa, which means “One Thousand Extraordinary Tales,” up until the dazzling and eter- nal title is established: Alf Laylah wa-Laylah, the “One Thousand and One Nights.” Because one thousand is dull—you wind up back in arithmetic—it’s both a lot and it’s finite. With one thousand and one, you pass into the unknown. You can always add to one thousand, but nothing can be added to nor take away from one thousand and one.

The most ancient sources are unambiguous. This organism is not made from one thousand extraordinary tales but passes through one thousand and one nights during which two young women, Scheherazade and Dunyazad, are to save the world from a king’s destructive madness. Who are they? What do they mean to each other? On this point, the most ancient sources are in disagreement. Over time, they become sisters. We can now confidently say so, since, opposite them, there are two brothers. That’s the scenario, and it’s simple: two sisters clash with two brothers. The latter are rational and intelligent. They do not act impulsively. They are too intelligent for that. But having already made use of all the resources intelligence has to offer, they see no other solution than the extermination of women and thus the end of the world. The former are also intelligent—even more intelligent—since they see no other solution than the pursuit of life. They devise a scenario—one that relies on addiction, addiction to fables. The scenario resumes every night and every day until the sisters prevail.

But I’m moving too fast. Let’s take a step back.

When it comes to the One Thousand and One Nights, as with many other things, we tend to forget the supporting roles (Dunyazad and Shah Zaman) in favor of the leading roles (Scheherazade and Shahryar). Yet the first king to be cheated on is indeed Shah Zaman, the younger brother, who inherited the kingdom of Samarkand, while his older brother’s kingdom extends from the islands of India to those of China. Longing for the presence of Shah Zaman, Shahryar sends a diplomatic mission to invite his brother to his palace. Shah Zaman gladly accepts. The preparations for the trip are just as splendid as the palaces and the gifts but, at long last, the time has come, and they are finally on their way. It is at this point that something unimaginable occurs, or, depend- ing on your perspective, something inevitable.

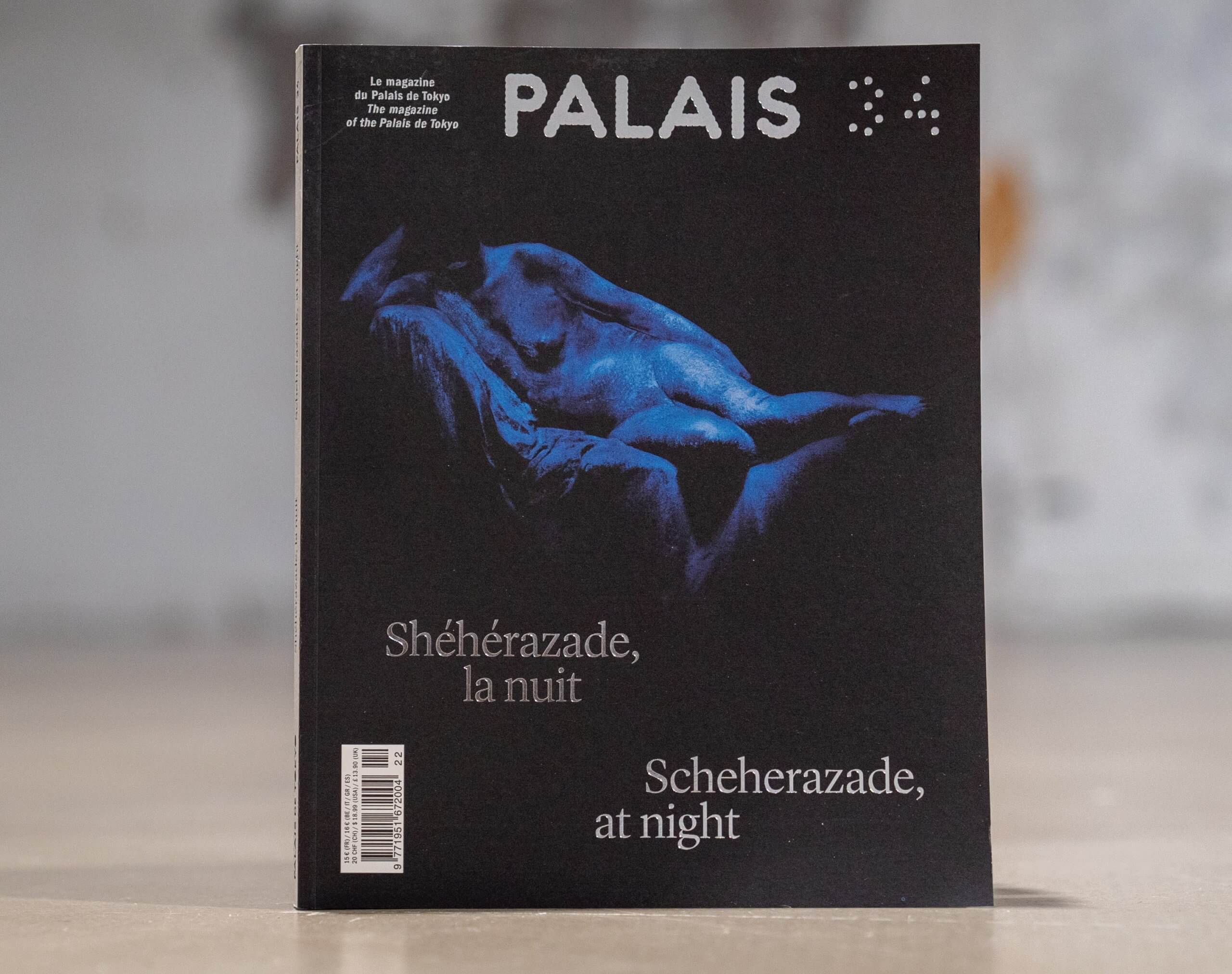

Near the middle of the night, Shah Zaman must retrace his steps to retrieve an object he has left behind. He returns to his palace and finds his wife stretched out on the royal bed, her body intertwined with that of a slave from the kitchen. This sight plunges him into darkness. He says to himself: “If this is what happens when I have barely left the city, what will this damned woman do when I go to visit my brother?” What follows is, regrettably, well-known: “He drew his sword and struck killing both his wife and her lover. Then he dragged them by the heels and threw them from the top of the palace to the trench below, before going back. The drum was struck and he ordered his escort to move off.”

He then sets out to meet Shahryar, his overinflated double, at whose palace everything is bigger, more intense, more extraordinary—even his wife’s betrayal. And the unlucky Shah Zaman is once again going to bear witness to a scene that has since established itself as one of the most well-known scenes of voyeurism in human history.

This one is perfect. King Shahryar, in a full expression of his power and his manliness, has gone hunting, leaving his melancholic brother to his darkness. The younger brother heads to a mashrabiya, providing him with an observatory where it is possible to see without being seen. But where the view is only partial, leaving to the imagination or to desire the care of piecing together the storyline. It does not disappoint: nothing less than a scene of group sex involving ten black slaves and ten white female servants, the queen, and the one known as Mas’ud.

When you think about it, it’s really quite a curious coincidence: two king-brothers cheated on. And yet, it’s a decisive one. Shah Zaman the melancholic, emaciated Shah Zaman, his face increasingly pale, regains some color, feels better. Shah Zaman feels better because he has witnessed a scene framed by a window, which is nothing other than a screen. Like those screens that, back then, were placed in front of the hearth—and, today, are placed in front of the world—in order to more efficiently release a heat that, without the screen, would burn us. Shah Zaman was burned by the first scene. He finds reassurance in the second scene, which comes to him mediated, represented, rescripted, projected, told in a different way.

Thus, a theory of fiction presents itself to us, a coherent one. There’s the real, which is too brutal—it hurts us, we don’t under- stand a thing. And when we understand, we don’t know what to do, we murder everyone. Fiction filters it and, all of a sudden, we understand better, we stop making a mess of things. We’re purged of our bad passions. Fiction cheats death: that is the theory of the frame-narrative, one that still enlivens us today. And it’s true that Shah Zaman feels better. He can finally converse with his brother to whom he had hardly said a word. He tells him everything about each of their misadventures to which he was witness. Shahryar wants to see. All the better, we will see with him. The two brothers become screenwriters. Manly, powerful, in a full expression of this manliness, they announce their departure for a fictional hunt, bringing about a reaction that we already know since, of course, history is repeating itself. Shahryar is devastated, but he does not step into darkness like his brother. He only brushes up against madness. He’s a true prince who must inform himself in order to act. Dominant males want to know, want to understand, before they act. They will get little for their efforts, because understanding is a disease for which narrative is the antidote.

They set out, “journeying for some days and nights” before stop- ping at the foot of “a tall tree in the middle of a meadow by the sea- shore.” Would they have been able to tell themselves that, in their palaces, while they were out hunting, their wives were shut away? That while their desires were being fulfilled elsewhere, out in the vast world, that maybe their wives needed to find some source of pleasure? Well, actually, no. They don’t tell themselves any of this. Here’s what we read—and it’s appalling:

“They left straight away and went back to Shahryar’s city, where they entered the palace and cut off the heads of the queen, the slave girls and the slaves.”

It’s a crushing defeat for intelligence. Shahryar commits the same impulsive crime as his brother, but after having taken the time to travel and get to know the world. He is unable to feel the mimetic effect that should have set him on the right path. He is straightforwardly rational. He is a sapiens in all of its destructive, violent, Machiavellian horror, putting the resources of intelligence to work for the destruction drive. He develops what, to my knowledge, is the first ever plan to extermi- nate a species. You know it as well as I do.

“Every night for three years, he would marry the daughter of a merchant or a commoner, deflower her and then kill her the next morning. He swore, ‘There is not a single chaste woman anywhere on the entire face of the earth.’ This led to unrest among citizens; they fled away with their daughters until there were no nubile girls left in the city.”

Then comes Scheherazade’s time.

She is even more intelligent than the king. “She had read books and histories, accounts of past kings and stories of earlier peoples, having collected, it was said, a thousand volumes of these, covering peoples, kings and poets.” Her father, the vizier, in charge of having Shahryar’s one-night wives executed, had hidden from her that the world was headed straight for its own downfall. As soon as she learns this, she decides to intervene and nominates herself for these macabre nuptials. Her father warns her by telling her the infamous story of the donkey, the ox, and the merchant. But there’s no need to explain the virtues of fictional mimetism to Scheherazade. She already gets it.

Time is of the essence, and faced with the imminence of the ultimate catastrophe, she has a script. A script for the repopulation of the world that begins by populating it with stories. The script involves her sister Dunyazad who will take care of the dialogic portion of each narrative. Scheherazade doesn’t have any doubts. She sees clearly into the future: “I shall then tell a tale that, God willing, will cause the king to stop his practice, save myself, and deliver the people.” She knows that the king’s perverted intelligence is disrupting his sleep, and that insomniacs can only find salvation in fables.

With Shah Zaman, we saw the image of the screen fiction, which protects from the brutality of the real, but does this through vague meanings and forms, and in doing makes it possible to bet- ter understand reality; Shah Zaman is also the image of cathartic fiction, which dresses the wounds and has a healing power. With Dunyazad, the theory of fiction known as the frame-narrative grows even richer. She tells us that fiction is not born from nothing. She sets forth from a script. Fiction requires a stimulus, a trigger, a ritual of immersion, without which its charm becomes a threat. Dunyazad is a threshold. She holds the door, opens it whenever necessary, but also knows how to close it. She is the border that opens onto fictional spaces and protects us from them. Scheherazade knows all of this, and she puts it to use.

And here we go—it will have only taken one night for the king to be made addicted to his new dope. “‘By God,’ the king said to himself, ‘I am not going to kill her until I hear the rest of this remarkable story.’” But he still hasn’t forgotten the previous story: revenge, murder, chaos. They’ll have to repeat, repeat, and repeat some more. Every night, pick up where they left off, with love and fables, beneath Dunyazad’s gaze. Repeat and vary, offer short fables, long ones, medium ones, use all available narrative resources—known ones and unknown ones—and, most importantly, never let dawn coincide with the end of the story. Repeat the mise en abyme, the nested constructions, make every- thing that does not exist in the present of presence coexist: the past, the future, spirits, talking animals… in order that, at last, this luna- tic king comes to understand. It will take nights—no one knows exactly how many, or rather, we all know how many—, it will take one thousand and one of them for Scheherazade to finally prevail. For her, her children, and all the children in the world to be saved, for the curse and the tumult to come to an end, for life to go on.

She saved the world. She is our heroine.

:

Translated by Jackson B. Smith.

This text reprises, abridges, and adapts a chapter from Lionel Ruffel, Trompe-la-mort (Lagrasse: Verdier, 2019). © Editions Verdier, 2019