SEARCH THE ENTIRE SITE

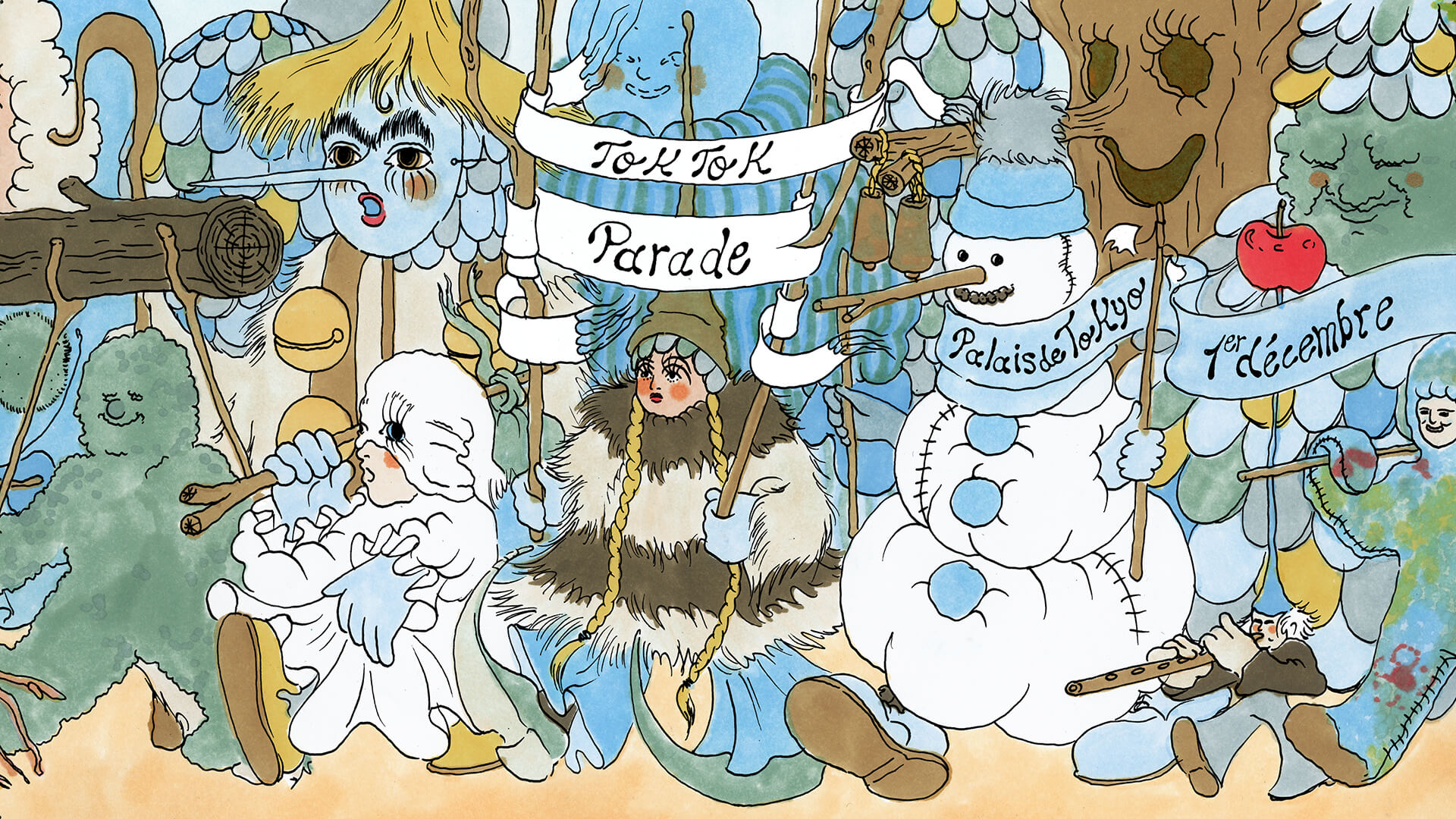

Tok-Tok Parade

A village fête at the Palais de Tokyo? Allow William Drummond to guide us through the Tok-Tok Parade. On the agenda for this collective moment of sharing and expression: workshops for all ages, afternoon snacks, narrated visits, a nap and, of course, the parade in the exhibition spaces!

You move through an exhibition like you would a forest. Everyone experiences it in a different way: you can see the trees as a whole or take an interest in a dead leaf on the ground; you can simply lie down and sense the space, recharge, or else think that you’d absolutely like to know the name of each tree. The exhibition is a space for resourcing, in the broadest sense of the term.

Ever since its beginning, the Palais de Tokyo has supported the idea of “mediation libre,” in other words, that it should be a place where visitors and mediators meet, in an attitude of dialogue and sharing. The works then make for a focal point around which we can express our own interpretations. Cultural mediation is not there to contradict, instead it aims at broadening discourse and making it a space for exchanges. This approach alters the authority in front of a work: who has the right to talk about it? Is it the artist, the curator, an art historian or else a lecturer, who provides information necessary for understanding a work, and who will be listened to? If art is there above all to ask questions, couldn’t we collectively suggest answers, and not just have a single person with a dominant one?

More generally, who has the right to express themselves in an institution? As well as “médiation libre” in exhibition spaces, the cultural mediation teams of the Palais de Tokyo have devised a large number of programmes around this idea of an encounter through art: a constellation of formats for visits, suited to a variety of audiences, and inclusive workshops, has been established inside and outside the walls of the art centre. Following on from these experiences, the Palais de Tokyo decided to set up the hamo, a space for cultural outreach, education and inclusion through art, and to create my job: being tasked with cultural mediation projects through artistic actions and practices. Artistic practices alongside cultural mediation schemes means being able to experience moments of life in institutional spaces. This enlarges the conception of the art centre which is not just a site for displaying works, but which also provides a space for the production of forms, where everyone is invited to express themselves through their practices. This does not mean that we are questioning the status of the artist. Instead, we consider that, just as visitors are made to feel free, with the choice to speak, artistic practice is able to open dialogues through actions, in a form of expression that can be more inclusive.

So, if we can all create in an institutional space, does that necessarily make it collective and/or participatory? A great variable in participatory and collective practices is that their results are uncontrollable: there is an orientation towards which the audience can be led; it’s a movement where the artist, project manager and/or mediator offer a framework, in which everyone can take their place to express themselves, and soon enough, things happen that cannot be controlled. This non-control creates an aesthetic, which can be more or less accepted, and which is so variable according to the audiences involved, that the presentation of the creations, and the way they are then exhibited, raises questions about their formal legitimacy. And that’s why it is interesting. In the end, what constitutes such a work is its moment of production, the social experience of collective creation, and not the end result. What emerges from it is simply the memory of this experience.

The Tok-Tok Parade was conceived as a village fête. The village, at the Palais, is more like a hamlet or “hamo”: an accumulation of small living spaces, on the outskirts of more central areas; a cluster of homes, somewhat sheltered, which has its own dynamic but which does not exist without the whole.

From the hamo, we examine the use of the institution’s spaces, and how this use can gradually open out towards practices that are more participatory and collective, more community-based, less hierarchised as well. For example, devoting a space to workshops means delimiting the practice. Perhaps we protect it in part by creating a dedicated space for it, but at the same time, we separate it from the space of professional artists, it’s strange; a bit like when we think that we should remain silent in exhibition spaces and only speak elsewhere. The fête of the hamo is a way to affirm a presence that is usually delimitated, a shift from the “activities space” to the “museum space,” an opportunity to inhabit these spaces, to make them resonate and, perhaps, to desacralize them.

The point is to create a large event allowing people to express themselves both in their uniqueness and shared identity. Quite organically, this took on the form of a parade: a ritualised assembly, in which everyone could make their own contribution, carry it themselves, while also carrying things that had been created collectively. And, as in many rituals, the artist, in the broadest sense of the term—who may be a musician, a cook, a costume designer, etc.—sets off a dynamic in which the inhabitants of the village, in other words the participants, would form this common identity together.

So, on the day of the Tok-Tok Parade, we set up a constellation of workshops, ephemeral creative actions aimed at instilling collective moments of sharing and expression, and then the participants paraded with their creations through the exhibition spaces. It should not be forgotten that not all participatory creation is collective creation; a very risky shift would be to use the participants in order to create a stunning parade. But the preceding artistic experience, which lasted three and a half hours, was essential, it was the heart of the event. The parade was just its result. It was thus necessary to find artists who complemented one another both in their fields of work and in their practice time. And for there to be zones of relaxation, zones of exuberance and zones of intimacy so that everyone could find something for themselves, in a shared way. With this in mind, we called on three artists for this edition: Léo Dupré, Valentine Gardiennet and Pia-Mélissa Laroche.

Léo Dupré suggested using large flags with cuts and combinations of textile elements that evoke winter. Each participant could contribute using their own iconography, which was combined with all the others. There was a clear craft aspect: sensorial elements, soft to the touch, and colours, with individual and collective variants. At the same time, there were small hoods for protection from the cold, which everyone could personalise: a space for individual freedom—my hood is my identity, which I will invest—but as everyone had a hood we were all part of the whole, despite it all.

Pia-Mélissa Laroche thought of bells entirely made of ceramic at the Palais de Tokyo, which each child could illustrate with natural materials (walnut stain, fusain, sanguine). A bell is a signal, conveying joy or danger—such as the fact that home, or a meal, is now not far, or else that snow is coming. What signal do we want to send in this winter, which has been a little lost today? And what is winter, in 2024, compared to iconographies inherited from past centuries? That is the entire question about a collective imaginary concerning this season which is raised by this parade. Families gathered in small spaces, like cocoons, and what could be heard was the jingling of bells from afar, at the back of the workshop.

With Valentine Gardiennet, the central idea was collective, while also being conceived for small children. There were large haystacks and giant soft toys, as white as snow, created by Valentine and which the children filled with straw. A cuddly toy provides a warm protection, comfort, while straw, used before winter, is a protection against frost in gardens or a preparation for the hibernation of animals. In this shifting winter, the children dyed these toys with many colours, in a moment of creative freedom. It was all about the pleasure of colour and a shared space. In the end, collaborating on a giant soft toy is also symbolic, because such a toy is highly personal, whereas in this case, we had a collective toy for the parade.

Our core competence is hospitality. So, we also invited participants to narrated visits, led by the mediators around the exhibitions, which brought to life this village fête, during which you also need to take a breather from time to time. It’s a bit strange to say, but we provide lots of possibilities for people to feel free not to do everything, to take breaks, to stop producing, and avoid constant consumption. Then came the snack, because any parade or big celebration requires a feast. Plenty of things were eaten, the families sat down together, and this moment was taken to refresh everyone’s energy before heading out for the parade.

We strolled around, each person responsible for their productions, hoods on their heads, bells in their hands, all carrying flags, dragging along huge soft toys through the entirety of the Palais. We then went down to the rotonda, the central space which has a highly specific echo. And, suddenly, everyone stopped, we slumped down on the sculpture-toys, dropped the flags, the bells went to sleep, and we entered hibernation. Then, softly, the bells began to jingle again. Winter was being replayed, then the spring that may arrive. We also reenacted the need to give ourselves strength to get through winter—or just to go back upstairs.

Once the parade was over, people spoke, perhaps a little more loudly, in the spaces, feeling more legitimate. This parade was truly there to reaffirm a presence. A presence that the children have told us about: their frustration at not being able to run in the exhibition spaces, not being able to touch, not being able to express themselves, to sing, or lie down. Well, during this parade, we made noise, yelled, ran and lay down. There we go.