SEARCH THE ENTIRE SITE

Interview with Naomi Beckwith

Can you share the intentions of the exhibition project that you had planned at the Palais de Tokyo?

Naomi Beckwith : The intention is to follow an instinctive idea: that French thinkers, writers, theorists, and philosophers have had a truly profound influence on American culture and artistic production.Yet this influence has not been traced in a deliberate way within France itself. I think it is high time to imagine an exhibition of American artists that focuses onhow the U.S. has received and transformed these theories and ideas, often in ways that were never really acknowledged on French soil. The idea is not to consider these artists merely as vessels passively receiving ideas in an unambiguous way. I am interested in what happens in translation: how certain notions are taken up, what becomes cogent and popular in the U.S., even when those ideas may never have gained much ground in France. I am drawn to the disparities, themisreadings, and also the poetry of it all — with the hope that audiences at the Palais de Tokyo might recognize something familiar, but also encounter something that feelsquite unfamiliar as well.

So how do you feel this intellectual and artistic relationship is still active today and among a young generation of artists?

NB: It’s definitely still very active. It feels like a new generational inheritance. When French thinkers began arriving in the U.S., there was an immediate impact. Michel Foucault, for example, spent time on the West Coast in the 1970s, while Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were being received on the East Coast as early as the 1950s and 60s. Almost immediately, artists interested in their work became close readers of it. Someone like Robert Morris became a deep thinker around Foucault, organizing seminars and studying himintensely. Later, you have Andrea Fraser, who has become an expert on Pierre Bourdieu. These are artists who are as much intellectual scholars as they are studio practitioners. But then those artists themselves became teachers. And what you see now is a reception of these ideas through that intermediary generation — the one that taught courses,incorporated readings into studio practice or art history classes, and passed the ideas along. The younger artists who studied with them became less focused on being precise scholars of French theory, but instead absorbed its ethos — the broader orientation, the attitude.

In the 1980s and 90s, for example, there was an explosion of institutional critique*: the idea that art could not only question general ideas in the world but also interrogate the frameworks and organizations around it, especially museums. Fred Wilson became one of the most significant figures in this regard. Today, I think it’s almost taken for granted that artists can question — even parody — institutions.

You’re saying that it’s kind of unconscious, it resides somewhere?

NB: The language is there but I’m not entirely sure that everyone fully understands the history of those ideas. We’ve come to take certain concepts for granted, like the notion that identities are not received butconstructed. That is 100% de Beauvoir: “A woman is not born but made.” We take that almost as gospel now, even though most people couldn’t quote the opening page ofThe Second Sex. In the U.S., we also understand now that race circulates both through the cultural environments people live in and are acculturated into, and through the structural forces of the state and its institutions. Again, these are discursive ideas that come from Foucault. One thing that has changed is the belated reception of Frantz Fanon in the U.S. His work has been deeply influential in thinking through anti-colonial and decolonial frameworks. Yet Fanon was not part of that first wave of reception for most artists. There were thinkers and teachers, like Mancho D. Awara, who were clearly engaging with his work, and writers like Édouard Glissant who referenced him.

In the U.S., it wasn’t until the 1990s that he became more widely discussed, and only in the 2000s that he became highly visible, openly quoted, even appearingon t-shirts. What fascinates me is how narrowly the category of “French theory” has been defined — as if it were a pantheon of thinkers beginning with the existentialists, crystallizing into a critical language with Foucault, and then moving to Jacques Derrida.

I’m also interested in how the Outre-mer are part of France, and in the intellectual work emerging from the Caribbean and North Africa — the exchanges within decolonial movements from regions that were legally part of France, but also deeply embedded in the global Black and African diaspora. I remember the day Aimé Césaire died: there was an impromptu gathering and reading in Harlem. A bookstore café was packed, and so many of us read passages of his work together.

Why do you think it is relevant to organize this exhibition today in France?

NB: There are two reasons why I think this exhibition is timely in France today. First, I’m curious about the reception of American art in France today. I do see formal and intellectual distinctions between what is happening on both continents. What kind of ripple effects can emerge when there’s an “American invasion”? Secondly, there is this recurring language in France about an American invasion, which I’ve always found amusing. I remember noticing a heightened anxiety around Americanization. It was most visible during presidential elections, when conversations about identity seemed to be seeping into both mass media and intellectual debates. People were talking about sexuality, race, cultural origins. And that discourse was often labeled “Americanization.” But I thought: this is hilarious. Americans only learned this critical language from French thinkers. Somehow, that lineage has been forgotten. And to be clear, there is not one unified line of French thought. On the contrary, there are many thinkers whose critical work clashes in fascinating and productive ways. So I don’t want to make an exhibition that suggests a neat, patrilineal or matrilineal genealogy. Instead, I want to remind people in France: this is your fault. Some people think “wokeism” comes from the U.S., but in many ways it is profoundly French.

This connects to something deeper: the rejection of certain terms for thinking about personhood in France. Why is it so difficult to talk about race? Why is it so hard to reconcile the colonial legacy with the idea of Frenchness? This rupture has had enormous political and social consequences, and yet there is still no adequate language to address it. And all the while, the frameworks we use in the U.S. to grapple with these issues come directly from French intellectual traditions. Everyone is afraid of differences — but what word did I just use? Différence, A French word.

Could you speak about the use value of ideas that originated in the French language for the artists in this show?

NB: The term critical theory is a mélange of theories that all questioned the centrality of Enlightenment thinking: Marxism, psychoanalysis, and, from France in particular, post-structuralist thought. Thinkers like Michel Foucault, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan, and those who followed them argued that the ways we had assumed human beings functioned were not necessarily accurate or ideal. Combined with Marxism and psychoanalysis, these ideas came to be grouped under the banner of critical theory.

And this was not just poetry. For some, it was real politics and real action. Yes, it circulated in academic contexts but most importantly, it gave people alanguage with which to critique what they had learned, to critique society itself. It offered a way to say: the way things are is not the way they always have to be. For artists, this meant challenging assumptions about aesthetics, about who produces great art, about the patriarchal frameworks in which art circulates. Every artist included here has a work or idea that still resonates, whether the piece dates from the 1960s or was commissioned for this show. Take Roland Barthes: his ideas about language as structure allowed artists not only to read texts differently but also to treat images — and even themselves — as texts to be deconstructed. That shift opened up space to think about queer desire, about what it means to live in a world that forecloses desire, and about how to produce images and languages of resistance. Artists like Tom Burr, for instance, use text and image to explore tensions between heteronormativity and queer desire. Similarly, Foucault’s questions around origins were later taken up by Édouard Glissant and others in the Caribbean, who asked: is there such a thing as a single origin?

Historical works like Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube remind us that art itself is not immutable; it changes in relation to viewers, technology, and context.This legacy continues in artists like Cameron Rowland, who use minimalist gestures to probe systemic questions. Char Jeré and William Pope.L embody a more contemporary sensibility: humor, self- deprecation, and criticality, often using their own bodies as sites of critique — whether around race, gender, or the very idea of personhood.

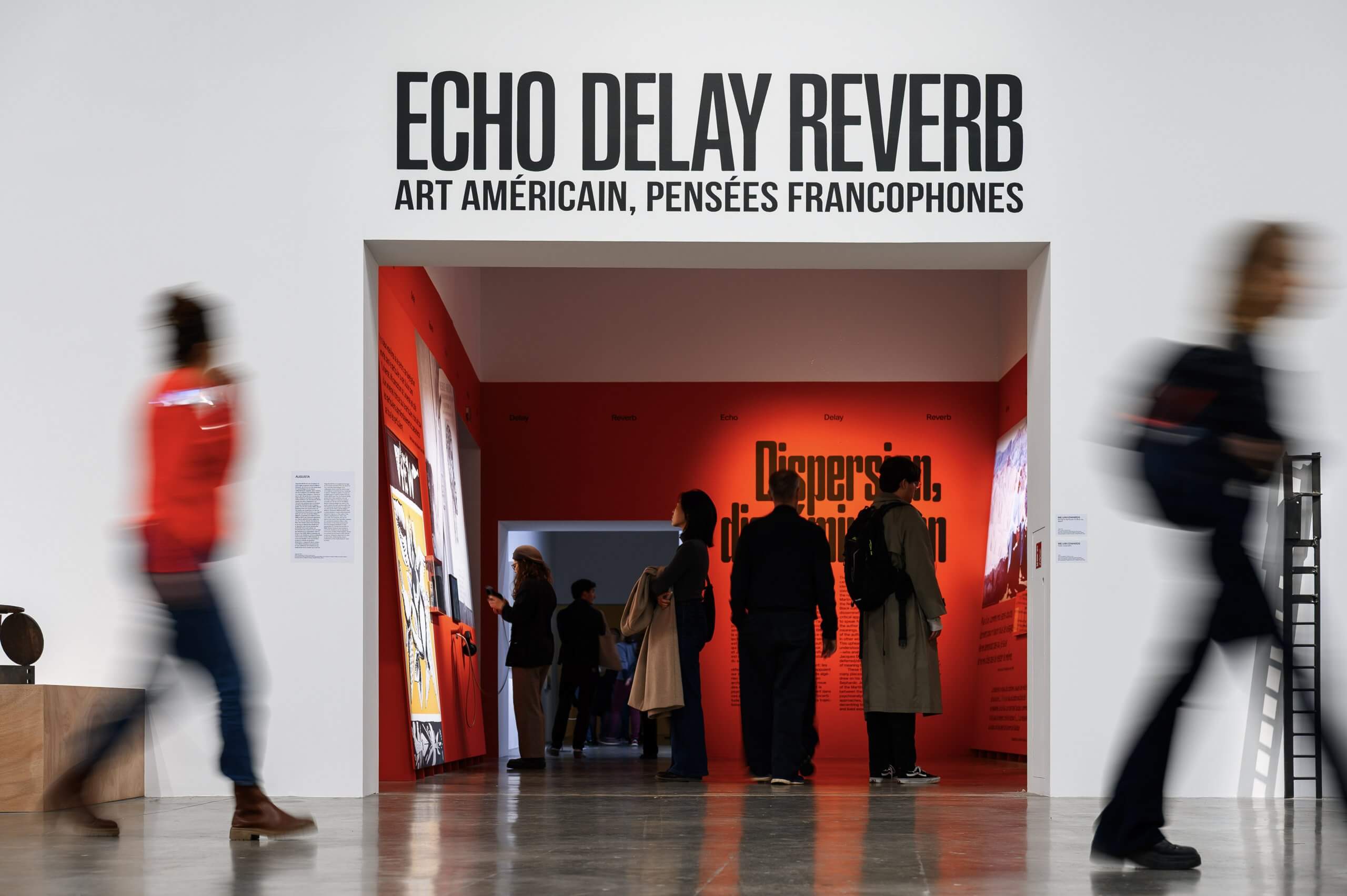

The show is structured around five thematic sections: dispersion, abjection, the non- human, institutional critique, and desiring machines. Can you tell us a bit more?

NB: We didn’t want to arrange the show chronologically but rather to foreground the ideas. This was the moment of the rise of conceptualism, when ideas became central. Many of the concepts developed during this high moment of critical theory are still circulating today. What we wanted to emphasize are the questions: What is human? Who is human? Who has historically been allowed to enjoy full human rights—and who still does today? What is our relationship to the institutions that define these categories, whether the home, the academy, or, for artists, the studio? And above all, how do we account for history in all of this?

What you see in this turn toward critical theory is that artists are no longer only concerned with self- expression or creating objects with intrinsic strength. They think holistically about the world they inhabit. What ties all these sections together is the insistence on critical theory not as an abstract discourse, but as a lived practice that continues to shape art, politics, and everyday life. It’s no longer just about producing art—it’s about being aware of how that art is made, how it circulates, and how its reception will always be framed by the structures in which it exists.